Spine Research Foundation does not endorse any treatments, procedures, products or physicians referenced in these patient fact sheets. This information is provided as an educational service and is not intended to serve as medical advice. Anyone seeking specific spine surgery advice or assistance should consult his or her spine surgeon, or locate one in your area.

Other Topics In

this chapter

What are spinal Deformities?

What causes Scoliosis?

Who gets Scoliosis?

What are the signs of Scoliosis?

What should be done?

What factors determine treatment?

What causes abnormal Kyphosis?

Brace treatment for Spinal Deformity

What does successful brace tratment requier?

What happens if the curve requires surgery?

A number of factors influence the recommendation for surgery:

Operative Considerations

Answers to questions commonly asked

Glossary of Medical Terms

Other Topics In

this chapter

What is a Congenital Spinal Deformity?

What causes the Congenital Spinal Deformity?

What are the signs of Congenital Spinal Deformity?

Heredity and associated conditions and Congenital Spinal Deformity

What should be done?

Treatment options

Summary

Glossary of Medical Terms

Other Topics In

this chapter

Osteoporosis and Compression Fractures

Osteoarthritis and Other Degenerative Conditions of the Spine

Scoliosis and Other Spine Deformities

Summary

Other Topics In

this chapter

Paralysis - a Myth!

Surgery is my only option!

Spine surgery leads to a bed ridden state for a long period with months of recovery

You cannot bend forwards or lift heavy weights or lie on a hard bed after surgery

Spine surgery is never successful and has high recurrence rates

Spine surgery is very expensive

Scoliosis & Kyphosis

The Scoliosis Research Society has prepared this booklet to provide patients, and in the case of children, their parents, with a better understanding of scoliosis, its diagnosis and management, using idiopathic scoliosis-the most common type-as a model. This information is intended as a supplement to the information your physician will provide you. Just as no two individuals are exactly alike, no two patients with a spinal deformity are the same. Therefore, your orthopaedic surgeon will be the most important source of information about the management of your particular spinal problem. It is beyond the scope of this booklet to discuss technical details concerning the surgical correction of scoliosis and kyphosis. Therefore, only a general review of these procedures has been included in the section dealing with surgery.

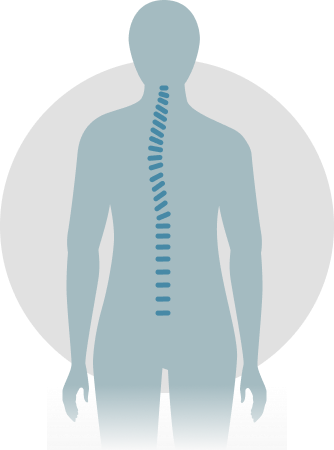

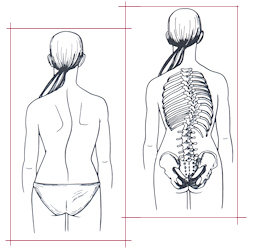

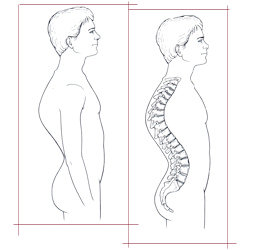

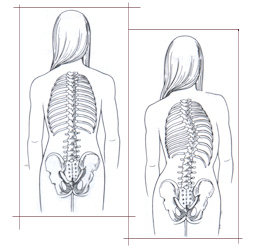

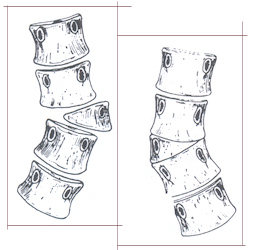

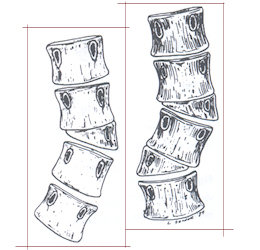

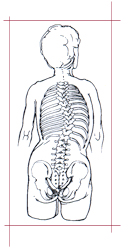

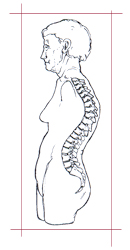

When the body is viewed from behind, a normal spine appears straight. However, when a spine with scoliosis is viewed from behind, a lateral or side-to-side curvature may be apparent. This gives the appearance of leaning to one side and should not be confused with poor posture. When the trunk is viewed from the side, the spine will demonstrate normal curves. The upper chest area has a normal roundback, or kyphosis, while in the lower spine there is a swayback, or lordosis. Increased roundback in the chest area is correctly called hyperkyphosis while increased swayback is termed hyperlordosis. Changes from normal on a side view frequently accompany scoliosis changes.

Eighty-five percent of people with scoliosis have the “idiopathic” type. “Idiopathic” means “no known cause.” It commonly affects adolescents as they complete the last major growth spurt. Idiopathic scoliosis frequently runs in families and may be due to genetic or hereditary influences. Idiopathic scoliosis may appear at any age but most often appears in early adolescence. At this age young people are reluctant to allow their bodies to be seen by parents and other adults. As a result, the Scoliosis Research Society and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons have endorsed school screening programs to detect scoliosis curves before they may become advanced.

Eighty-five percent of people with scoliosis have the “idiopathic” type. “Idiopathic” means “no known cause.” It commonly affects adolescents as they complete the last major growth spurt. Idiopathic scoliosis frequently runs in families and may be due to genetic or hereditary influences. Idiopathic scoliosis may appear at any age but most often appears in early adolescence. At this age young people are reluctant to allow their bodies to be seen by parents and other adults. As a result, the Scoliosis Research Society and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons have endorsed school screening programs to detect scoliosis curves before they may become advanced.

In contrast to idiopathic scoliosis, there are several less common types of scoliosis which do have a known cause. These curves may be due to defects of spinal vertebrae already present at birth (“congenital scoliosis”), disorders of the central nervous system such as cerebral palsy, muscle diseases (muscular dystrophy), disorders of connective tissue (Marfan’s syndrome), and chromosome abnormalities (Down’s syndrome).

In childhood, idiopathic scoliosis occurs in both girls and boys. However, as children enter adolescence, girls are five to eight times more likely to have their curves increase in size and require treatment.

- One shoulder may be higher than the other.

- One scapula (shoulder blade) may be higher or more prominent than the other.

With the arms hanging loosely at the side, there may be more space between the arm and the body on one side. - One hip may appear to be higher or more prominent than the other.

- The head is not centered over the pelvis. (Fig. above)

- When the patient is examined from the rear and asked to bend forward until the spine is horizontal, one side of the back appears higher than the other.

In ninety percent of cases, scoliotic curves are mild and do not require active treatment. In the growing adolescent, it is very important that the curves be monitored for change by periodic examination and standing X-rays as needed. Increases in spinal deformity require evaluation by an orthopaedic surgeon to determine if brace treatment is required. In a small number of patients, surgical treatment may be needed.

- Age in years.

- Bone age (the maturation of bone is not always the same as the chronological age).

- Degree of curvature.

- Location of curve in the spine.

- Status of menses/puberty.

- Sex of the patient.

Worsening of curve.

Kyphosis (roundback) is commonly used to refer to excessive curvature of the thoracic spine when viewed from the side. Excessive roundback deformity may simply be postural and can often be corrected with exercises and proper posture. A small percentage of patients with kyphosis have more rigid deformities than the postural type, which are associated with wedged vertebrae. This type is called Scheuermann’s kyphosis and is much more difficult to treat than postural kyphosis. Its cause is unknown. Bracing may be recommended for the immature adolescent with Scheuermann’s kyphosis.

Kyphosis (roundback) is commonly used to refer to excessive curvature of the thoracic spine when viewed from the side. Excessive roundback deformity may simply be postural and can often be corrected with exercises and proper posture. A small percentage of patients with kyphosis have more rigid deformities than the postural type, which are associated with wedged vertebrae. This type is called Scheuermann’s kyphosis and is much more difficult to treat than postural kyphosis. Its cause is unknown. Bracing may be recommended for the immature adolescent with Scheuermann’s kyphosis.

Brace treatment (orthosis) is recommended for increasing scoliosis or kyphosis in the skeletally immature patient. Bracing is recommended for moderate scoliosis or abnormal kyphosis. There are many types of braces, all designed to prevent curves from increasing as the adolescent grows. The orthosis acts as a buttress for the spine to prevent the curve from increasing during active skeletal growth. Braces will not make the spine straight, and cannot always keep a curve from increasing. However, bracing is effective in halting curve progression in a significant percentage of skeletally immature adolescents.

- Early detection while the patient is still growing.

- Mild to moderate curvature.

- Regular examination by the orthopaedic surgeon.

- A well-fitted brace.

- A cooperative patient and supportive family.

- Maintenance of normal activities, including exercise, dance training, and athletics, with elective time out of the brace for these activities as supervised by the physician.

When a young person exhibits a worsening spinal deformity, surgical treatment is indicated to improve the deformity and to prevent increasing deformity in the future. The most common surgical procedure is a posterior spinal fusion with instrumentation and bone graft. The term “instrumentation” refers to a variety of devices such as rods, hooks, wires and screws, which are used to hold the correction of the spine in as normal an alignment as possible while the bone fusion heals. The instrumentation is rarely removed.

When a young person exhibits a worsening spinal deformity, surgical treatment is indicated to improve the deformity and to prevent increasing deformity in the future. The most common surgical procedure is a posterior spinal fusion with instrumentation and bone graft. The term “instrumentation” refers to a variety of devices such as rods, hooks, wires and screws, which are used to hold the correction of the spine in as normal an alignment as possible while the bone fusion heals. The instrumentation is rarely removed.

- The area of the spine involved

- Severity of scoliosis

- Presence of increased or decreased kyphosis

- Pain (rare in adolescents, more common in adults)

- Growth remaining

- Personal factors.

- A comprehensive preoperative conference

- Donating your own blood (if possible)

- Good nutritional status before and after surgery

- Exercise program before and after surgery

- Positive mental attitude

A lack of calcium will not cause scoliosis.

Poor posture does not cause scoliosis.

Carrying a heavy book bag does not cause scoliosis.

Scoliosis is not usually painful in adolescence, but can become so in adulthood.

Braces do not make the spine straight.

Smoking does interfere with bone healing.

The metal implant (spinal instrumentation) does not activate the metal detectors at airports, does not rust, and is not subject to rejection by the body.

Surgery does not interfere with normal childbearing.

Spinal deformities are not contagious.

At present, there is no known prevention for spinal deformities.

- Adolescent scoliosis: lateral spinal curvature that appears before the onset of puberty and before skeletal maturity.

- Adult scoliosis: scoliosis of any cause which is present after skeletal maturity. Autograft: any tissue transferred from one site to another in the same individual (iliac bone from the pelvis is commonly used to supplement the fusion mass). Autologous blood: blood collected from a person for later transfusion to that same person. This technique is often used prior to elective surgery if blood loss is expected to occur. This may avoid the use of bank blood from unknown donors and significantly reduces the risk of acquiring transmitted diseases.

- Autotransfusion: the practice and technique of transfusing previously drawn autologous blood back to the same patient.

- Cervical spine: that portion of the vertebral column contained in the neck, consisting of seven cervical vertebrae between the skull and the rib cage.

- Compensatory curve: in spinal deformity, a secondary curve located above or below the structural curvature, which develops in order to maintain normal body alignment.

- Congenital scoliosis: scoliosis due to bony abnormalities of the spine present at birth. These anomalies are classified as failure of vertebral formation and/or failure of segmentation. Decompensation: in scoliosis, this refers to loss of spinal balance when the thoracic cage is not centered over the pelvis.

- Discectomy: removal of all or part of an intervertebral disc (the soft tissue that acts as a shock absorber between the vertebral bodies).

- Double curve: two lateral curvatures (scoliosis) in the same spine. Double major curve: describes a scoliosis in which there are two structural curves which are usually of equal size. Double thoracic curve: a scoliosis with a structural upper thoracic curve, as well as a larger, more deforming lower thoracic curve, and a relatively nonstructural lumbar curve. Hemivertebra: a congenital anomaly of the spine caused by incomplete development of one side of a vertebra resulting in a wedge shape.

- Hysterical scoliosis: a non-structural deformity of the spine that develops as a manifestation of a psychological disorder.

- Idiopathic scoliosis: a structural spinal curvature for which cause has not been established.

- Inclinometer: an instrument used to measure the angle of thoracic prominence, referred to as angle of trunk rotation (ATR).

- Infantile scoliosis: curvature of the spine that develops before three years of age. Juvenile scoliosis: scoliosis developing between the ages of three and ten years. Kyphoscoliosis: a structural scoliosis associated with increased roundback.

- Kyphosis: a posterior convex angulation of the spine as evaluated on a side view of the spine. Contrast to lordosis.

- Lordoscoliosis: a lateral curvature of the spine associated with increased swayback.

- Lordosis: an anterior angulation of the spine in the sagittal plane. Contrast to kyphosis.

- Lumbar curve: a spinal curvature whose apex is between the first and fourth lumbar vertebrae (also known as lumbar scoliosis).

- Lumbosacral: pertaining to the lumbar and sacral regions of the back.

- Lumbosacral curve: a lateral curvature with its apex at the fifth lumbar vertebra or below (also known as lumbosacral scoliosis).

- Neuromuscular scoliosis: a form of scoliosis caused by a neurologic disorder of the central nervous system or muscle.

- Nonstructural curve: description of a spinal curvature or scoliosis that does not have fixed residual deformity.

- Pedicle: bony process projecting backward from the body of a vertebra, which connects with the lamina on either side.

- Posterior fusion: a technique of stabilizing two or more vertebra by bone grafting.

- Primary curve: the first or earliest curve to appear.

- Risser sign: used to indicate spinal maturity, this refers to the appearance of a cres-centic line of bone formation which appears across the top of each side of the pelvis.

- Sacrum: curved triangular bone at the base of the spine, consisting of five fused vertebrae known as sacral vertebrae. The sacrum articulates with the last lumbar vertebra and laterally with the pelvic bones.

- Scoliometer: a proprietary name for an inclinometer used in measuring trunk rotation. Scoliosis: lateral deviation of the normal vertical line of the spine which, when measured by X-ray, is greater than ten degrees. Scoliosis consists of a lateral curvature of the spine with rotation of the vertebrae within the curve.

- Spinal instrumentation: metal implants fixed to the spine to improve spinal deformity while the fusion matures. This includes a wide variety of rods, hooks, wires and screws used in various combinations.

- Spondylitis: an inflammatory disease of the spine.

- Spondylolisthesis: an anterior displacement of a vertebra on the adjacent lower vertebra. Structural curve: a segment of the spine that has fixed lateral curvature.

- Thoracic curvature: any spinal curvature in which the apex of the curve is between the second and eleventh thoracic vertebrae.

- Thoracolumbar curve: any curvature that has its apex at the twelfth thoracic or first lumbar vertebra.

- Thoracolumbosacral orthosis (TLSO): a type of brace incorporating the thoracic and lumbar spine.

- Vertebral column: the flexible supporting column of vertebrae separated by discs and bound together by ligaments.

Congenital Scoliosis Kyphosis

The Scoliosis Research Society has prepared this booklet to provide patients and /or their parents with a better understanding of a particular type of spine deformity-congenital, its diagnosis and treatment. This information is intended as a supplement to the information your physician will provide. The behavior of congenital spinal deformities may be very different from one individual to another though a number of general statements can be made. However, your orthopaedic surgeon will be the most important source of information for you or your child’s particular case. It is beyond the scope of this booklet to discuss in detail the technical aspects of all the various surgical procedures that may be needed. But, general concepts about the surgical treatment are discussed. Additionally, it must be stressed that congenital spinal deformities are much different than the more common idiopathic type of deformity, requiring different evaluation and treatment.

These are spinal deformities-scoliosis (side-to-side) or kyphosis (excessive round-back)-that are caused by abnormally formed or joined vertebrae, which an affected person is born with. The type of deformity that is seen depends on which direction and where the abnormal vertebrae are positioned within the spinal column. The normal spine should be straight when viewed from behind.

These are spinal deformities-scoliosis (side-to-side) or kyphosis (excessive round-back)-that are caused by abnormally formed or joined vertebrae, which an affected person is born with. The type of deformity that is seen depends on which direction and where the abnormal vertebrae are positioned within the spinal column. The normal spine should be straight when viewed from behind.

When viewed from the side, there should be a gentle roundback (kyphosis) in the thoracic (chest part) spine and lordosis (swayback) in the lumbar (lower part) spine. Scoliosis or increased kyphosis or lordosis are abnormalities and in congenital cases are caused by asymmetric growth of the abnormal vertebrae.

As mentioned above, the key factor causing the spine to curve is the asymmetric growth of the abnormally formed vertebrae. The abnormalities can be classified as: Type I-Failures of Formation (hemivertebrae or incompletely formed vertebrae) and Type II-Failures of Segmentation (vertebrae that are abnormally joined together). There also can be combination of the two. A hemivertebra causes one side of the spine to grow more than the other. Vertebrae that are joined together on one side (unsegmented bar) result in tethering of the growth on that side, again causing the spine to curve.

As mentioned above, the key factor causing the spine to curve is the asymmetric growth of the abnormally formed vertebrae. The abnormalities can be classified as: Type I-Failures of Formation (hemivertebrae or incompletely formed vertebrae) and Type II-Failures of Segmentation (vertebrae that are abnormally joined together). There also can be combination of the two. A hemivertebra causes one side of the spine to grow more than the other. Vertebrae that are joined together on one side (unsegmented bar) result in tethering of the growth on that side, again causing the spine to curve.

It is important to note that although the abnormal vertebrae are present at birth, there may not be much of an abnormal curvature at first. This occurs with growth. But even with growth, many of these affected spines may curve very little or not at all. In fact in spines with multiple abnormal vertebrae, the main effect may be significant stunting of trunk growth rather that increasing curvature. There may be very little increase in the curvature until the adolescent growth spurt.

- Side-to-side curvature or abnormal roundback or swayback.

- Skin abnormalities on the back – hairy patches, dimples, discolored areas.

- Abnormally formed or functioning arms or legs.

- Abnormal functioning bowel and/or bladder.

- Uneven shoulders, waist or hips.

- Disproportionate length of the trunk to the legs.

- Head not centered over the pelvis.

- Hump(s) on the back that are seen when the person bends forward.

Congenital spinal deformities are generally not considered to be hereditary. However, congenital spinal abnormalities may be associated with other conditions that are.

Congenital spinal deformities are generally not considered to be hereditary. However, congenital spinal abnormalities may be associated with other conditions that are.

Therefore, ordinarily, parents of a child with an isolated congenital spinal deformity are not at increased risk for having another child with it. Currently, there is no way to prevent congenital spinal deformity and it is not entirely clear why these abnormalities occur.

Because of the events that occur during the development of the embryo and fetus a number of associated abnormalities can be seen with congenital spinal deformity.

The most common are:

- Klippel-Feil syndrome (congenital fusion of 2 or more vertebrae in the neck) – 25%

- Kidney-bladder system abnormalities – 30%

- Spinal cord abnormalities – 15%

- Congenital heart problems – 12%

The most common are:

Proper diagnosis of the abnormality should be made as soon as it is recognized. This may involve special X-rays, MRI, ultrasound or other tests. The results of these studies help identify associated problems and provide information about how the spine deformity may behave in the future. Usually a period of what has been called “controlled observation” should occur also to see how the abnormality is behaving. This is done with periodic physical exams and X-rays. If steady increase in the curvature or other functional problems arise, the appropriate surgical procedure(s) should be undertaken.

Proper diagnosis of the abnormality should be made as soon as it is recognized. This may involve special X-rays, MRI, ultrasound or other tests. The results of these studies help identify associated problems and provide information about how the spine deformity may behave in the future. Usually a period of what has been called “controlled observation” should occur also to see how the abnormality is behaving. This is done with periodic physical exams and X-rays. If steady increase in the curvature or other functional problems arise, the appropriate surgical procedure(s) should be undertaken.

One of the big differences between congenital and idiopathic deformities is that braces are not effective in congenital deformities. The only effective treatment is to eliminate or modify the asymmetric growth of the abnormal vertebrae most commonly accomplished by spinal fusion. The surgery may have to be done when a child is quite young in order to control a progressive deformity.

Parents are understandably concerned that early fusion, which arrests growth of the spine within the fused segment, may lead to stunting of trunk growth. While this is true to an extent, trying to regain trunk height by correcting a very severe curvature after completion of growth is not possible and may be dangerous. Even if early surgery is done, additional procedures may be necessary if the original surgery does not completely control the curve. In actively growing children both anterior (in the front) and posterior (in the back) fusion may be necessary to control the deformity. These techniques can be applied to both scoliosis and kyphosis. Achieving a spinal fusion requires either autograft (a person’s own) or allograft (someone else’s) bone, a bone substitute or a combination of 2 or more of these sources.

Parents are understandably concerned that early fusion, which arrests growth of the spine within the fused segment, may lead to stunting of trunk growth. While this is true to an extent, trying to regain trunk height by correcting a very severe curvature after completion of growth is not possible and may be dangerous. Even if early surgery is done, additional procedures may be necessary if the original surgery does not completely control the curve. In actively growing children both anterior (in the front) and posterior (in the back) fusion may be necessary to control the deformity. These techniques can be applied to both scoliosis and kyphosis. Achieving a spinal fusion requires either autograft (a person’s own) or allograft (someone else’s) bone, a bone substitute or a combination of 2 or more of these sources.

Associated problems (e.g. spinal cord abnormalities) may require specific treatment either before, at the same time, or even after the surgical treatment for the spinal deformity. Sometimes, the spinal deformity itself may cause damage to the spinal cord (e.g. congenital kyphosis due to failure of formation) rather than an intrinsic spinal cord abnormality.

Controlled observation – This is accomplished by periodic physical exams and X-rays and is continued without specific treatment as long as no increase in the curve occurs and is continued until skeletal maturity. (It is also done after surgical treatment).

Surgical treatment – Currently all surgical procedures for the treatment of congenital spinal deformity involve fusion of at least 2 vertebrae. These operations may involve fusing the curve without correction (in situ fusion) with or without internal fixation (implanted rods, hooks, etc), correction of the curve with internal fixation plus fusion, removal of a hemivertebra with internal fixation, or fusion of the convex side of the curve only. As mentioned above, growing children often require anterior and posterior fusion to adequately control the curve. It is absolutely essential that the fusion heals, otherwise the procedure will fail and the curve will not be controlled. Newer procedures that do not involve a fusion are being developed but are considered experimental at this time. There are many factors that must be considered in choosing the best procedure for you or your child. The choices available should be discussed with your orthopaedic surgeon.

Post-operative casts or braces – Usually in children either a brace or cast will be used for a period of time after the surgery to help immobilize the spine so that the fusion heals properly. Braces can also help align and balance the adjacent and normal vertebrae which have been drawn into the curve. In older children and adults, rigid internal fixation may eliminate the need for a cast or brace.

Congenital spinal deformities are caused by the asymmetric growth of vertebral abnormalities that a person is born with. While some affected persons never develop a significant curvature, many do and the curvature may become very severe if not recognized and treated appropriately. A number of potentially important associated conditions can exist along with the congenital spinal deformity. Usually a period of observation is needed to assess the behavior of the deformity. If the deformity worsens, the only effective treatment is surgical. A number of operations can be done but at this time all involve fusing a segment of the spine. The surgery is performed when it has been determined that the curvature needs to be controlled, sometimes when a child is quite young. Continued observation until at least the end of growth is necessary for all patients with congenital spinal deformities.

- Anterior fusion: fusion performed from the front of the spine by removing the discs and packing the disc spaces with bone graft

- Allograft bone: bone obtained from another person

- Autograft bone: bone obtained from the same person (pelvis, rib) and transferred to a different place in the body

- Congenital spinal deformity: curvatures caused by abnormally formed vertebrae that a person is born with

- Hemivertebra: an incompletely formed vertebra-a failure of formation

- Internal fixation: rods, hooks, screws, wires and/or plates that are used to stabilize the operated part of the spine

- Klippel-Feil syndrome: a congenital fusion of 2 or more vertebrae in the neck

- Kyphosis: a curvature of the spine toward the back

- Lumbar spine: lower spine between the chest and the pelvis

- Posterior fusion: fusion performed from the back of the spine.

- Thoracic spine: upper spine from the bottom of the neck to the last rib

- Unsegmented bar: an abnormal connection between 2 or more vertebrae, usually on one Side

Ageing Spine

The unrelenting changes associated with ageing progressively affects all structures of the spinal units. The degenerative process starts early during the first decade of life at the disc level. Discal degeneration is associated with biochemical changes followed by macroscopic alterations including tears and fissures, which may lead to discal herniation, the main cause of radiculopathy in the young adult. Facet joint changes are usually secondary to discal degeneration. They include subluxation, cartilage alteration and osteophytosis. Facet hypertrophy and laxity, associated with discal degeneration, and enlargement of the ligamentum flavum progressively create narrowing of the spinal canal as well as degenerative instabilities such as spondylolisthesis and scoliosis, which are the main causes of neurogenic claudication and radiculopathy in old persons. Vertebral bodies are the static elements of the spinal unit. With advancing age, osteoporosis weakens the bony structures and facilitates bone remodeling and rotatory deformities. Finally, ageing of bone, discs, facets, ligaments, and muscles may ultimately lead to rotatory scoliosis, destabilization, and rupture of equilibrium.

Osteoporosis is a decrease in bone mass, more commonly seen in women in the post-menopausal period. It is a decrease not only in the mineral component, but also in what is called the organic component of bone. The extent of the osteoporosis can only be estimated on plain x-rays and must be confirmed by specific bone density tests or, in some cases, by bone biopsy to confirm its presence. About 15-20 million people have osteoporosis and over one half million suffer spinal fractures due to osteoporosis each year. These fractures can occur with minimal trauma or no trauma at all.

Back pain is the most common presenting symptom of this condition and x-rays may show wedge or compression fractures of the vertebrae. MRI or CT scans may be necessary for further evaluation of these fractures. Fortunately, most of these are successfully treated with just medications to control the pain, but the underlying osteoporosis should also be addressed once it is recognized. The treatment of osteoporosis itself is rapidly evolving. Current measures include combinations of calcium, vitamin D and estrogen. Calcitonin is used in some cases to inhibit bone resorption and fluoride has also been tried in an attempt to increase bone mass. More recently, drugs like fosomax, one member of the bis-phosphonate family of drugs which help to maintain and possibly increase bone mass, have been used in the treatment of osteoporosis.

In addition to medications, other things that help control pain and prevent worsening deformity are devices like certain kinds of back braces. Although these usually do not correct the wedging of the bone, they do support the spine and may decrease secondary muscle spasm. In rare cases, surgical treatment may be necessary to control the pain, improve the deformity, or decompress the nerve roots or spinal cord.

New techniques to treat the problem of compressed vertebrae include procedures like vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty. In these two techniques the vertebrae are injected with a bone cement (vertebroplasty) to improve the strength of the bone. Alternatively, cement can be injected after improving the wedging by inflating a balloon inside the vertebra body and filling the space with that cement (kyphoplasty). Both procedures require at least sedation and local anesthesia, but sometimes require general anesthesia during their performance. The procedures are done percutaneously (using only very tiny incisions) using x-ray control. As with any other surgical procedures, there are certain risks inherent in performing these procedures. However, early results for these minimally invasive techniques are encourageing.

As a final thought, it is very important to confirm the diagnosis of osteoporosis rather than other possible conditions, such as infections, other metabolic bone diseases and benign or malignant bone tumors, prior to embarking on a course of treatment.

Degenerative discs and facet joints

Degeneration of the discs and the small joints of the spine (facet joints) is, generally a normal part of the ageing process in the spine. The process as seen on x-rays may not cause any symptoms but can, in some individuals, be associated with significant back and/or leg pain. In those patients with advanced arthritis/degeneration, x-rays show marked narrowing of the discs as well as arthritic changes in the facet joints. Initial treatment is generally focused on improving muscle support of the back with exercises, the use of anti-inflammatory medications, and braces. If the initial pain is severe, a short period of bed rest may be necessary to control the acute pain, with gradual return of activities as soon as possible. Severe progressive symptoms associated with degenerative changes may require surgical treatment to alleviate the symptoms.

Spinal stenosis

As the arthritis/degeneration worsens, the spinal canal (the space which holds the spinal cord and nerve roots) can narrow as a result of these changes in the discs and facet joints, as well as thickening of one of the large ligaments that crosses the space between two vertebrae. These structures then press on the nerves in the spinal canal. This constriction, or stenosis, can lead to pain in the legs while walking and standing and is usually relieved by sitting or lying down. These kinds of symptoms are known as neurogenic claudication, which must be differentiated from the same kind of pain down the legs that is caused by circulatory problems, arthritis of the hips, or diabetic nerve problems. Spinal stenosis is diagnosed specifically by CT or MRI scans. Sometimes EMG and nerve conduction tests are used to differentiate this condition from diabetic nerve involvement.

Nonsurgical treatment consists of anti-inflammatory medicines, exercise, physical therapy and occasionally steroid/local anesthetic injections. These injections can be into the soft tissues, such as the muscles and ligaments, into the spinal canal (epidural), or specific nerve root blocks. If these procedures do not relieve the symptoms then surgical decompression of the involved vertebrae may be necessary. This surgery is quite effective and allows patients to walk farther and stand longer. It involves decompressing the nerve roots by removing the roof of the spinal canal (laminectomy) and enlarging the spaces where the nerve roots exit the canal (foraminotomy). A fusion of the affected vertebrae may also be necessary if instability is present. Remember that a spinal fusion is a procedure which welds the spinal segments together using bone, either from the iliac crest (pelvis) or from the bone bank. In the majority of cases, a metal implant consisting of screws and rods is used to help maintain stability at these segments while the fusion heals.

The hospital stay is relatively short without fusion and a bit longer with it. In either case, particularly if a patient had some debilitation preoperatively, a short stay in a rehab facility, to regain strength and mobility, may be needed. The actual details of post-discharge care, resumption of normal physical and athletic activities, driving, and the possible use of a brace will be provided by the patient’s surgeon based on specific issues of each individual’s case.

Herniated lumbar disc

Ruptured, slipped or herniated discs are terms that are commonly used for the same thing. Herniated discs most commonly occur in the 20 to 50 year old group, but can occur at all ages. In older patients, they may again be associated with arthritis and nerve root compression. Typically, most people will have an episode or two of low back pain not necessarily associated with a traumatic event and subsequently develop leg pain, commonly known as sciatica. Discs rupture and herniated because of degeneration and tears in various parts of the disc.

Symptoms are frequently self-limited and respond to restriction of activity, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, short periods of bed rest, if the pain is particularly severe, then exercise and physical therapy. If the symptoms do decrease, gradual return of full activities may take about four weeks. Although steroid medications that have been used to treat the sciatica in the past are still valuable drugs for this purpose, they are often associated with significant complications and should be used only briefly, if at all. In patients whose symptoms last longer than several weeks, who have significant and/or progressive leg weakness or loss of bowel/bladder function, an MRI scan or a CT scan with or without a myelogram should be performed to identify the abnormality.

If there is no improvement within one to three months with non-operative measures or if leg pain or weakness persists or worsens, surgical treatment may be necessary. The most common procedure for this condition is a discectomy in which a small incision is made and the disc is removed. Relief of symptoms is frequently quite dramatic. Healthy patients undergoing this surgery can have it done as an outpatient procedure, but occasionally the side effects of anesthesia and pain medication used post operatively require admission to the hospital for a day or two. After the surgery, some recovery is necessary but gradual return to activities is the rule and is allowed in seven to ten days. Return to work and sports varies and should be discussed with the patient’s surgeon.

Cervical Degenerated Disc Disease

Neck pain and stiffness frequently occur in the ageing spine. This is due to arthritic changes in the joints and degenerated discs, which can be easily seen on regular x-rays. When the neck pain is associated with pain and/or numbness or weakness in the arm or hand, further workup may be needed as these symptoms indicate pressure on one or more nerve roots. Evaluation entails a thorough neurologic examination and imaging using an MRI and/or CT scan with or without a myelogram.

Treatment consists of immobilization with a collar, non-steroidal antiinflammatory medications, and physical therapy. Occasionally, halter traction is used to help as well. If the symptoms are significant and persistent despite these non-operative measures and/or a significant neurological deficit is occurring, then surgical treatment will be necessary. This generally entails what is called an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, with possible removal of the degenerative bony spurs that occur around the border of the discs. The fusion is performed with either iliac crest or bank bone and the vertebrae involved are fixed together using a plate and screws. If multiple levels are involved, a posterior decompression and stabilization with plates and screws and a fusion may be performed as an alternative. It should be recognized that if there is severe stenosis of the canal in the cervical spine, significant pressure on the spinal cord itself (not just the nerve roots) can occur and may lead to loss of the ability to walk and/or loss of bowel and bladder function and control. This is known as cervical myelopathy. When it occurs, it usually progresses slowly and diagnosis is often delayed. Decompression and stabilization are necessary if the spinal cord is being compressed.

Adult Idiopathic and Degenerative (de novo) Scoliosis

Scoliosis in the adult is a curvature of the spine that can occur for two reasons. The first is that it may be a residual (left over) scoliosis that started when the patient was younger (idiopathic scoliosis). The degenerative or de novo type is a form of scoliosis that starts after age 40 and is thought to be the result of arthritis or degeneration of the spine, with changes in alignment due to degeneration of the discs and the facet joints. It is known that some of the curves that start off in a growing child will worsen as an adult. It has been suggested that curvatures which are 50 degrees or more after skeletal maturity may worsen by about one degree a year. Curves of less than 30 degrees really don’t worsen. This is otherwise known as the natural history, or what happens to the spine if no treatment is ever rendered. The de novo curves may also progress a few degrees a year, particularly if there is osteoporosis and a sequential collapse of the vertebrae

Scoliosis in the adult is a curvature of the spine that can occur for two reasons. The first is that it may be a residual (left over) scoliosis that started when the patient was younger (idiopathic scoliosis). The degenerative or de novo type is a form of scoliosis that starts after age 40 and is thought to be the result of arthritis or degeneration of the spine, with changes in alignment due to degeneration of the discs and the facet joints. It is known that some of the curves that start off in a growing child will worsen as an adult. It has been suggested that curvatures which are 50 degrees or more after skeletal maturity may worsen by about one degree a year. Curves of less than 30 degrees really don’t worsen. This is otherwise known as the natural history, or what happens to the spine if no treatment is ever rendered. The de novo curves may also progress a few degrees a year, particularly if there is osteoporosis and a sequential collapse of the vertebrae

Since both types can be associated with arthritis, many patients will have back pain and muscle fatigue, as well as possible leg pain. Larger curves (over 40 degrees) should be checked periodically for increases in curve size. Worsening of the scoliosis will cause loss of height along with the other symptoms previously mentioned. Evaluation of the process involves the use of regular x-rays, MRI scans and possibly CT-myelograms. These studies help identify stenosis and other abnormalities in the spine and around the nerve roots and spinal cord that may be associated with the spinal deformity.

Treatment consists of arthritis medications such as non-steroidals for pain relief, physical therapy for improving overall function, and exercise to improve strength. If the medications and therapy do not work, cortisone/ local anesthetic injections in the muscle, joints or spinal canal may be an option. Surgical treatment is frequently necessary if the curve or other symptoms worsen. The type of surgical procedure varies depending on the curve type and size and whether there is any associated spinal stenosis. The most common surgery is performed through the back (posterior) and consists of a spinal fusion with metal implants and bone graft (from the pelvis or the bone bank), with or without decompression of the nerve roots. Sometimes the surgery may need to be performed in the front of the spine (anterior) for better stability, correction and healing. Occasionally a combination of both anterior and posterior surgery is necessary to correct the problem. The hospital stay for such procedures depends on the type(s) of procedures done and the overall condition of the patient. Many adults undergoing scoliosis surgery smoke or have medical conditions that may affect healing and recovery time. A brace is frequently used after surgery. Details regarding return to normal physical and athletic activities, post-operative care and other issues should be discussed with the patient’s surgeon.

Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis is a slippage of one vertebra on another. There are two common types. The most common form develops in childhood and is symptomatic in a teenager or in an adult who has developed it during teenage years. The second type is degenerative spondylolisthesis, caused by disc and joint deterioration. This form generally becomes noticeable in the 50 and older age groups. Both types may present with spinal stenosis or nerve root compression. People with spondylolisthesis may have back and sometimes leg pain. As the arthritis worsens, the spinal canal can narrow as a result of the enlarged facet joints, degenerated discs and enlarged ligaments, which causes pressure on the nerve roots and spinal cord in the spinal canal. These events can lead to leg pain while walking or standing. As mentioned earlier, the cause of pain must be differentiated from circulation problems, arthritis of the hip or nerve problems associated with diabetes.

Generally, spondylolisthesis is diagnosed with regular x-rays. Nerve root compression is detected by the use of CT or MRI scans. EMG and nerve conduction tests may be needed to differentiate other diagnoses from spinal stenosis.

Non surgical treatment consists of anti-inflammatory medicines, exercise and physical therapy, plus occasional injections as mentioned previously. If these measures fail and a patient continues to have significant symptoms, surgical treatment may be necessary. That involves decompressing the nerve roots and/or spinal cord by removing the roof of the spinal canal (laminectomy) and enlarging the spaces for the nerve roots (foraminotomy). A spinal fusion is performed, again using either iliac crest or bank bone. Correction of the slippage and/or maintenance of stability until the fusion heals is done via the use of metal implants.

Those patients requiring surgery need to be in the hospital for 4 or 5 days and, again, recovery and healing will be affected by the patient’s general medical condition and smoking history. Details of post-operative care and resumption of activities should be discussed with the surgeon.

Kyphosis

Kyphosis is a forward bending of the spine, which produces a hump of the back or a roundback deformity. Some people have postural kyphosis, which is not rigid. Others will have a more rigid or structural type of kyphosis. Diagnoses such as pre-existing Scheuermann’s kyphosis (which can be made worse by superimposed compression fractures) are frequently responsible for the production of this deformity. However, multiple compression fractures alone can produce the deformity due to collapsed vertebrae, as is commonly seen in older osteoporotic women. Methods of evaluation are regular x-rays, MRI and CT scans and myelograms.

Kyphosis is a forward bending of the spine, which produces a hump of the back or a roundback deformity. Some people have postural kyphosis, which is not rigid. Others will have a more rigid or structural type of kyphosis. Diagnoses such as pre-existing Scheuermann’s kyphosis (which can be made worse by superimposed compression fractures) are frequently responsible for the production of this deformity. However, multiple compression fractures alone can produce the deformity due to collapsed vertebrae, as is commonly seen in older osteoporotic women. Methods of evaluation are regular x-rays, MRI and CT scans and myelograms.

Back pain is the most common presenting symptom, but patients may also complain of increasing deformity and loss of height. Current treatment consists of pain medication, but if the patient has osteoporosis, treatment for this must be addressed as well. As mentioned previously, there are numerous medications now available for this purpose, which may improve the pain symptoms but cannot correct the wedged bone or a significant spinal deformity. Braces may support the spine and decrease muscle spasm. If there is any doubt as to the underlying cause of the compression fractures a biopsy may be necessary to rule out such things as tumors, infection or other conditions. If these conservative measures do not help, surgery may be necessary to control pain and improve deformity or decompress nerve roots. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty mentioned previously may be of value in these conditions, but more extensive fusions and instrumentations are often necessary to achieve treatment goals.

The normal process of ageing causes various changes all along the spine, which may lead to one or more of the conditions discussed above. The prevention of osteoporosis with its subsequent complications is the mainstay of prevention against many, but not all, of these conditions. A number of these can be cause, or at least worsened, by the presence of weak vertebrae. Others are caused by the natural process of ageing which can be superimposed on a pre-existing spinal condition. While pain in various areas of the spine may be a nuisance, neurologic problems like weakness and numbness require urgent and proper evaluation and treatment to prevent serious permanent loss of function. Maintaining a degree of physical fitness and muscle strength as well as preventing and/or treating osteoporosis will go a long way in managing the inevitable changes in the spine that occur with the normal ageing process.

Misconceptions

Lets bring an end to the wrong notions...

Modern techniques of surgery have ensured its safety and efficacy like enhanced illumination, better magnification, easy vision in the nooks and corners of complex anatomy, additional technology such as high-end microscope, high speed drill and intra-operative neural monitoring. In today’s scenario, paralysis remains only a myth!

Majority of patients are treated conservatively, without surgery. It is imperative for you to get yourself professional consultation. Visit us now…

Mostly patients are made to get out of bed by 24-48 hours after surgery; post-operative management there on leads to a steady time bound recovery.

no long-term restrictions: after few weeks of surgery – climb stairs, lift heavy weights; using a two-wheeler, three-wheeler, all are allowed. You can continue to do the things you love.

current reoperation rates are very rare - surgery provides you a permanent long-lasting solution in most cases.

SRF helps you out if you are unable to meet the expenses of your treatment. Contact us now here.